15. Modern Missions

| Key Dates # |

|

|---|

| 1705 | Dutch missionaries reach out to Tamil India - in spite of European opposition

|

| 1718 | David Brainerd, American missionary among indigenous tribe, born

|

| 1727 | Revival among Count Nikolaus Ludwig Zinzendorf and Hussite Moravian refugees he

had taken in. Moravian missionary movement begins.

|

| 1792 | William Carey, "Expect great things from God. Attempt great things for God".

|

| Particular Baptist Society for Propagating the Gospel among the Heathen

founded, later called the Baptist Missionary Society

|

| 1795 | London Missionary Society founded

|

| 1799 | Church Missionary Society founded

|

| 1808 | Henry Martyn publishes the New Testament in Hindustani

|

| 1801 | William Carey's Bengali New Testament published

|

| 1813 | David Livingstone, missionary and explorer in Africa, born

|

| 1832 | Hudson Taylor, missionary to China and founder of China Inland Mission, born

|

| 1835 | Adoniram Judson translates the Bible into Burmese

|

| 1848 | Mary Slessor, missionary to Nigeria, born

|

| 1860 | Charles (CT) Studd, missionary to China, India and Africa, born

|

| 1892 | John ("Praying") Hyde, American missionary to India, arrives in the Punjab.

|

| 1927 | Jim Elliot, missionary to Auca Indians in Ecuador, born

|

| 1960 | Founding of Youth with a Mission; "to know God and make Him known"

|

Background

The 19th Century was the greatest century for Christian missions. In 1793 the modern

missionary movement was launched by William Carey. In just 100 years Bible translations

multiplied from 50 to 250 and mission organisations from 7 to 100. Protestant missionaries were

sent out to every corner of the world. Within a century, the number of professing Christians had

more than doubled from 215 million to 500 million. Christian outreach became truly global.

What prompted the modern missions movement?

- Spiritual awakening, revivalism in Europe and North America, leading to concern about

the fate of the unevangelised, and obedience to the Great Commission of Jesus to all

Christians, Matthew 28:18-20. An awareness the Gospel was not just for Europeans.

- Exploration. During the 1500s and 1600s, missions from Europe were carried on almost

exclusively by Roman Catholics, especially Jesuits and Franciscans. These efforts were

supported by the major maritime powers - Spain, Portugal and (later) France. By the

early 1600s, the British East India Company was trading in India. Great Britain gradually

began to control land, and a century later nearly all of India was incorporated into the

British Empire. England, with its growing commercial interests, had become the

dominant maritime power in the world. News of Captain Cook's explorations in the South

Pacific expanded peoples' curiosity and understanding of the world. When William Carey

read The Last Voyage of Captain Cook, it stirred his interest in missions.

- Colonialism (eg the Scramble for Africa), raised awareness of mission fields and opening

up of new areas (some risks, eg 3 Cs, Civilisation, Christianity & Commerce).

- Easier forms of travel and communication.

The missionaries of the past two centuries were incredibly tough. They made sacrifices and

endured hardships that we can hardly imagine. They went out expecting to change the world.

Most of them died young. The average life expectancy of a missionary to Africa was 8 years.

Johan Krapf, missionary to East Africa, lost his wife and children to disease within months. The

Church in Africa was literally built upon the bones of countless missionaries and martyrs.

Some Influential Christians During This Period

David Brainerd (1718-1747) Making the Most of Three Years

Brainerd was born at Haddam, Connecticut. He was orphaned at fourteen and studied for three

years (1739-1742) at Yale. He then prepared for the ministry, being licensed as a Presbyterian

minister in 1742. In 1743 decided to devote himself to missionary work among indigenous

Americans. Supported by the Scottish "Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge," he worked

first at Kaunaumeek, an Indian settlement about 20 miles from Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and

subsequently (until his last illness), among the Delaware Indians in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

His heroic and self-denying work, both for the spiritual needs and welfare of the Indians, wore

out a naturally weak constitution, and on 19 October 1747 he died at the house of his close

friend, Jonathan Edwards, in Massachusetts. He is believed to have died of tuberculosis.

Throughout his life, Brainerd was regarded by some as being unqualified to work in missions, due

to the state of his health, yet he was regarded as a pioneer in missions, despite being suffering

from self-doubt, depression and physical illness. His life's legacy is an encouragement to all

Christians to serve God regardless of physical limitations.

Brainerd's "Journal" was published in 1746. It contains detailed meditation on the nature of the

illness that eventually led to his death and its relation to his personal walk with God. Brainerd

wrote a lot about prayer in the life of the Christian. Edwards published "An Account of the Life

of the Late Rev. David Brainerd, chiefly taken from his own Diary and other Private Writings", in

1749; it quickly became a missionary classic.

The Moravian Missionary Movement

"I have but one passion - it is He, it is He alone. The world is the field and the

field is the world; and henceforth that country shall be my home where I can be

most used in winning souls for Christ." - Count Zinzendorf

Count Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf was born in 1700 into wealth and a noble family. As a

young man, he developed a passion for spreading the gospel. He attended Wittenberg University

with the aim of earning a law degree, but felt a call to serve Christ. In 1719 he was powerfully

impacted by a painting of Christ wearing a crown of thorns. An inscription below the painting

read, "All this I did for you, what are you doing for me?" This was a decisive moment in his life,

moving him to finally choose against the life as a nobleman and enter Christian ministry.

On 13 August 1727,during a communion service on Zinzendorf's estate, the Holy Spirit moved

powerfully. Zinzendorf led others (many of them Hussite refugees) in beginning a prayer

meeting that lasted one hundred years. Beginning with a deep conviction for the evangelization

of the world, the Spirit-filled prayer meeting deepened in passion for the lost. This was

undeniably the force behind the great Moravian missions movements that followed.

The Moravians explained their motivation for missions as follows (1791):

"The simple motive of the brethren for sending missionaries to distant nations was and is

an ardent desire to promote the salvation of their fellow men, by making known to them

the gospel of our Savior Jesus Christ. It grieved them to hear of so many thousands and

millions of the human race sitting in darkness and groaning beneath the yoke of sin and

the tyranny of Satan; and remembering the glorious promises given in the Word of God,

that the heathen also should be the reward of the sufferings and death of Jesus; and

considering His commandment to His followers, to go into all the world and preach the

gospel to every creature, they were filled with confident hopes that if they went forth in

obedience unto, and believing in His word, their labor would not be in vain in the Lord.

They were not dismayed in reflecting on the smallness of their means and abilities, and

that they hardly knew their way to the heathen whose salvation they so ardently longed

for, nor by the prospect of enduring hardships of every kind and even perhaps the loss of

their lives in the attempt. Yet their love to their Saviour and their fellow-sinners for

whom He shed His blood, far outweighed all these considerations. They went forth in the

strength of their God and He has wrought wonders in their behalf."

The first two Moravian missionaries sailed for the West Indies on 8 October 1732. Their purpose

was to follow Jesus' command, "As the father has sent me so send I you." The only way to reach

the slaves of the West Indies was to become incarnated into their lives. These two therefore

sailed with the objective of selling themselves into slavery to reach slaves with the Gospel.

When Moravians reached their destinations, they would unload their belongings and burn their

ships, refusing to look back or abandon their goal of evangelisation.

The Moravian Brethren were responsible for some of the most inspiring and sacrificial stories of

mission history. One of every sixty Moravians went out as a missionary, planting missions in the

Virgin Islands, Greenland, North America, South America, South Africa, and Labrador.

William Carey (1761-1834) - "The father of modern missions"

In the late 18th century, most of the world had never heard the Christian message. England in

the 1790s was in the grip of a mixture of fear and excitement: fear, because just across the

Channel in France a revolution had overthrown the monarchy and seemed determined to destroy

the Christian religion as well (starting with the corrupt official church); excitement, because

Christians felt that these upheavals might herald great events. Captain James Cook's voyages

had made Englishmen aware of exotic lands scarcely known before.

Starting in 1784, first Baptists and then other nonconformists throughout the English Midlands

had been meeting on the first Monday of every month to pray for a revival that would lead to

the spread of the gospel 'to the most distant parts of the habitable globe'. Confronted by

political upheaval, widening geographical horizons and new currents of spiritual life brought by

the Great Awakening, Christians began to believe God was about to do something new. A young

Northamptonshire shoemaker named William Carey believed that the return of Christ was

imminent, if only God's people persevered in their new commitment to prayer and began to

translate that commitment into action. By the close of the 19th century Christianity covered

the globe and missions was embedded in evangelical church culture. This change was due

largely to Carey.

Carey was born in 1761. His family had no money for education, but at the age of 12 he taught

himself Latin. At 16, around the time of his conversion, he became an apprentice cobbler. As

he learned his new trade, he began to study the Bible.

Carey was consumed with learning and often fasted to save money for books. He accepted a call

to pastor a Baptist church, but worked as a cobbler to make ends meet. He concluded from

Bible study that the Great Commission was still in force and that the Church was responsible to

take the Gospel to the world - an idea resisted by many church-leaders who believed the Great

Commission mandate applied only to the Apostles' generation and had ceased. When Carey

decided to go to India (1793), his father, his wife and people in his church disagreed.

Before he left, Carey did two things that produced a huge impact. First, he gave one of the

most influential sermons of all time: "Expect Great Things [from God]; Attempt Great Things

[for God]". Second, he wrote a short book (87 pages) with a big title: "An Inquiry into the

Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathen"; its influence has been

compared to that of Luther's 95 theses.

Carey went to India, with his still resistant wife. He first worked at Bengal under the umbrella

of the British East India Trading Company. But the company's workers were driven by making

money, not saving souls; they were opposed to missions, which proved a hindrance to Carey's

work. So he moved to Serampore (near Calcutta) under Danish oversight to work with a teacher

and printer who had followed him to India. They made a powerful team planting churches,

translating and printing Bibles, founding colleges and reforming the culture around them. Carey

taught himself several local languages and published their grammars and lexicons. He oversaw

the Bible's translation into six languages and parts of it into two dozen others.

Carey paid a high price for his service. The climate and conditions were hard - God often

prepares His servants by the discipline of hardship. He struggled with government bureaucracy

and buried two wives and several of his children. But he never left India, in 41 years.

Carey pioneered missions strategies that we take for granted today: cross-cultural

communication; Bible translation and printing; evangelism; church planting; education; medical

and relief work; and recruitment and sending of missionaries. He also tried to end the customs

of infanticide and widow burning (cremating the wife of a dead man with his body). Even before

Carey died, his example was elevating missions in the eyes of Christians everywhere. By not

quitting in tough times, Carey was used by God beyond anyone's expectations. The keys to his

spiritual success were faith, determination and persistence.

Later in the nineteenth century, the ideals of Carey and others like him were eclipsed as

missions succumbed to the influence of European colonialism and racialism. In Carey's own day,

other missionaries criticized Serampore for relying on Indian nationals. History has largely

vindicated Carey's view: countries where the church is strongest today are generally those where

national Christians were/are encouraged from an early date to be evangelists to their own and

neighbouring peoples.

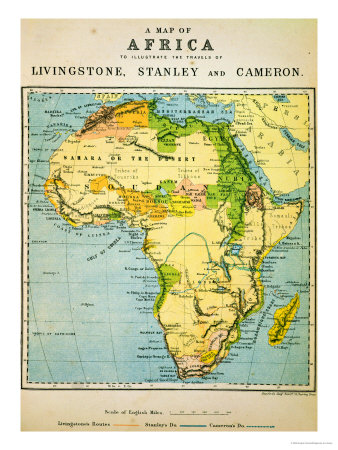

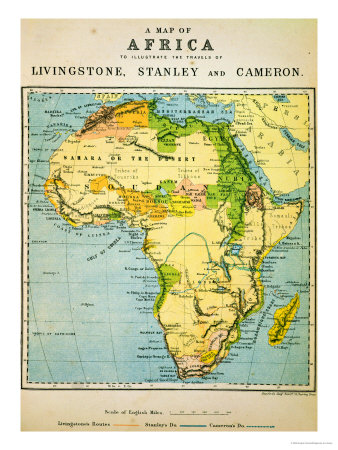

David Livingstone (1813-1873)

Livingstone

His Travels in Africa

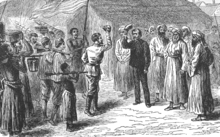

Meeting with Stanley

David Livingstone was born at Blantyre, south of Glasgow, on 19 March 1813. At age 10 he began

studying medicine and theology (while working) and decided to become a missionary doctor. In

1841, he was sent to the edge of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa. In 1845, he married

Mary Moffat, daughter of a fellow missionary.

Livingstone became convinced of his mission to reach new people in the unknown heart of Africa

(known then as the "Dark Continent") and introduce them to Christianity, as well as freeing

them from slavery. He first came into contact with the slave trade as a missionary in the 1840s.

Appalled at the treatment of slaves, he began sending eye-witness accounts back to Britain. His

reports were influential. The East African slave trade centred round the slave markets on

Zanzibar and other ports along the coast. Captured Africans were sold there and sent to work as

slaves on spice plantations in the Arabian Peninsula and Indian Ocean Islands. The British

Government pressured the Sultan of Zanzibar and he closed the slave market in 1873, just six

weeks after Livingstone's death. This ended the legal trade in slaves on the East Coast of Africa.

In 1849 and 1851, Livingstone travelled across the Kalahari, exploring the upper Zambezi River.

In 1852, he began a four-year expedition to find a route from the upper Zambezi to the coast.

This filled huge gaps in western knowledge of central and southern Africa. In 1855, he

discovered a spectacular waterfall which he named 'Victoria Falls', after Queen Victoria. He

reached the mouth of the Zambezi on the Indian Ocean in May 1856, becoming the first

European to cross the width of southern Africa.

Returning to Britain (national hero), Livingstone did many speaking tours and published his

'Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa' (1857). He left for Africa again in 1858. For

the next five years carried out explorations of eastern and central Africa for the government.

His wife died of malaria in 1862 and in 1864 he was ordered home by the government.

At home, Livingstone publicized the horrors of the slave trade, securing private support for

another expedition to central Africa, searching for the Nile's source and reporting further on

slavery. This expedition lasted from 1866 until Livingstone's death in 1873. After nothing was

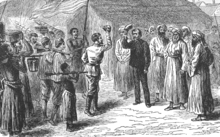

heard from him for many months, Henry Stanley, an explorer and journalist, set out to find him.

This resulted in their meeting near Lake Tanganyika in October 1871, during which Stanley

uttered the famous phrase: 'Dr Livingstone I presume?' With new supplies from Stanley,

Livingstone continued his efforts to find the source of the Nile. His health had been poor for

many years and he died (on his knees, in prayer, in Zambia) on 1 May 1873. His body was taken

back to England and buried in Westminster Abbey; his heart was buried in Africa.

Critics of Livingstone point to the limited number of conversions under his ministry, and his shift

in emphasis from evangelization to exploration; however without men and women like

Livingstone continents such as Africa would not have been opened up to those who followed,

who planted Christian communities.

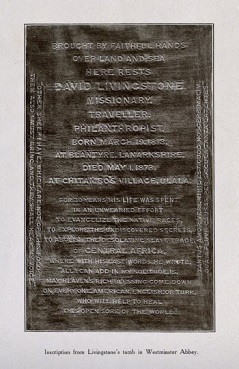

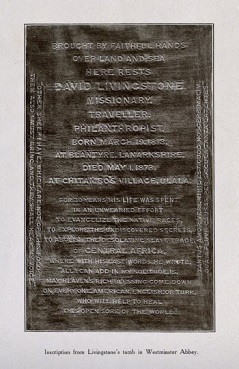

BROUGHT BY FAITHFUL HANDS OVER LAND AND SEA HERE RESTS DAVID LIVINGSTONE, MISSIONARY,

TRAVELLER, PHILANTHROPIST, BORN MARCH 19 1813 AT BLANTYRE, LANARKSHIRE, DIED MAY 1, 1873

AT CHITAMBO'S VILLAGE, ULALA. FOR 30 YEARS HIS LIFE WAS SPENT IN AN UNWEARIED EFFORT TO

EVANGELIZE THE NATIVE RACES, TO EXPLORE THE UNDISCOVERED SECRETS, TO ABOLISH THE

DESOLATING SLAVE TRADE, OF CENTRAL AFRICA, WHERE WITH HIS LAST WORDS HE WROTE, "ALL I

CAN ADD IN MY SOLITUDE, IS, MAY HEAVEN'S RICH BLESSING COME DOWN ON EVERY ONE, AMERICAN,

ENGLISH, OR TURK, WHO WILL HELP TO HEAL THIS OPEN SORE OF THE WORLD"

From Livingstone's Journals:

- "I place no value on anything I have or may possess, except in relation to the kingdom of

Christ. If anything will advance the interests of the kingdom, it shall be given away or

kept, only as by giving or keeping it I shall promote the glory of Him to whom I owe all

my hopes in time and eternity"

- "I am prepared to go anywhere, provided it be forward."

- "If we wait till we run no risk, the gospel will never be introduced into the interior (of

Africa)."

Hudson Taylor (1832-1905)

James Hudson Taylor was born in Yorkshire, England in 1832. After a brief period skepticism

during his teenage years, he came to Christ by reading a Christian tract in his father's pharmacy.

A few months after his conversion, he committed himself to God's work. He sensed a calling to

China and began studying medicine. He lived on as little as possible, trusting God for his every

provision.

In 1853, the twenty-one-year-old Taylor sailed for China as part of a new missionary

organisation. He arrived in Shanghai and immediately began learning Chinese. Funds from home

rarely arrived, but he was determined to rely upon God for his every need and never appealed

for money to his friends in England. He often told friends, "Depend upon it. God's work, done in

God's way, will never lack for supplies." In those days, foreigners were not permitted into the

interior of China; they only were allowed in five Chinese ports. Taylor, however, was burdened

for millions of Chinese who had never heard of Christ. Ignoring the political restrictions, he

travelled along inland canals preaching the gospel.

In 1858 he married Marie Dyer, an English orphan who was working in a school for Chinese girls in

Ningpo. By 1860, foreigners were able to legally travel anywhere in China, missionaries were

allowed, and the Chinese were permitted to convert to Christianity. At a time when tremendous

opportunities were opening up in China, ill health forced Taylor, with his wife and small

daughter, to return to England. What seemed at first to be a setback in his work turned out to

be a step forward. While in England recovering his health, Taylor was able to complete his

medical studies. He revised a Chinese New Testament and set up a new missions organisation,

"China Inland Mission".

Twenty-two people accompanied Taylor back to China in 1866. Hardships multiplied: Taylor's

daughter died from water on the brain; the family was almost killed in the Yang Chow Riot of

1868; his wife died in childbirth; his second wife died of cancer; sickness and ill health were

frequent. Yet, the China Inland Mission continued its work of reaching millions for Christ and

became the largest missions organisation of its day. By 1895 it had 641 missionaries plus 462

Chinese helpers at 260 mission stations. Under Taylor's leadership, the Mission supplied over

half of the Protestant missionaries in China. During the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, 56 of them

were martyred and hundreds of Chinese Christians were killed. The missionary work did not

diminish, however, and the number of missionaries quadrupled in the following decades.

Chinese Christians proved remarkably resilient under Communism. They did not die out but

multiplied in one of the greatest expansions in church history.

Mary Slessor of Calabar (1848-1915)

Born in 1848 in Scotland, Mary Mitchell Slessor was the second of seven children. When she was

eleven years old, Mary started working to help provide for her family. Her wages were soon the

primary source of income, working 10 hour days to make ends meet. She was close to her

mother as they prayed continually for God's provision and protection.

Mary became a Christian at a young age. She was not well-educated, but loved to read, and

would stay up late soaking up any book she could find. She loved reading the Bible most of all,

studying the message of Jesus Christ and his life in the gospels. Mary dreamed of doing pioneer

work in the remote interior of Africa. At the time, missions work was mainly for men, so she

was encouraged to get involved with home missions. It was her older brother who was planning

to go as a missionary, but when Mary was 25 years old, he died. She wondered if maybe she

could go in his place. Early in 1874 the news of the death of David Livingstone stirred the church

and created a great wave of missionary excitement. Mary was then determined to go.

In 1875, Mary was accepted to go with the Calabar Mission (located within present day Nigeria).

She was stationed in Duke Town as a school teacher. She learned Efik, the local language,

enjoyed teaching, but her heart was set on doing pioneer work. After three years, she was sent

home on furlough due to malaria. When she returned, she was given a new task in Old Town,

where she had the freedom to work by herself and live as she pleased. Mary decided to live with

local people. Her childhood of poverty made this lifestyle seem fairly normal.

Mary quickly learned about the culture of the local tribes. Witchcraft, spiritism and tribal

customs were hard to fight against. One custom that broke her heart was 'twin-murder'. People

believed twins were a result of a curse caused by an evil spirit who fathered one of the children.

Both babies were brutally murdered and the mother was shunned from society. Overwhelmed

and depressed, she knelt and prayed, "Lord, the task is impossible for me but not for you. Lead

the way and I will follow." Mary rescued many twins and ministered to their mothers. God gave

her favor with the tribesmen, and Mary eventually gained a respect unheard of for a woman.

After only three more years, Mary was sent home on yet another furlough because she was

extremely sick. As she returned home, she took Janie, a 6-month-old twin girl she'd rescued.

She was home for over three years, staying to look after her mother and sister, who were ill.

While there, she spoke to many churches and shared stories from Africa. She finally returned to

Africa, more determined than ever to pioneer into the interior. She was bold in her ministry and

fearless as she travelled from village to village. Mary rescued hundreds of twin babies thrown

out into the forest, prevented tribal wars, stopped the practice of trying to determine guilt by

making suspects drink poison, healed the sick, and told the people about the great God of love

whose Son came to earth to die on the cross that sinful men might have eternal life.

While in Africa, she received word that her mother and sister had died. Now she had no one

close to her. She was overcome with loneliness. But she also found a sense of freedom, writing,

"Heaven is now nearer to me than Britain, and no one will be anxious about me if I go

upcountry." In August 1888, she went north to Okoyong the 'up-country' of West Africa, an area

that had claimed the lives of missionaries in the past, but she was sure that "pioneer work" was

sometimes best accomplished by women, who were less threatening to unreached tribespeople

than men. For 15 years she stayed with the Okoyongs, evangelizing and teaching them, nursing

them and being a peacemaker, they eventually made her a judge for the whole region.

During a period of sick leave Mary met Charles Morrison, a missionary teacher serving in Duke

Town. She accepted his marriage proposal, but the marriage never happened. His health did

not even allow him to stay in Duke Town, and, for Mary, missionary service came before

personal relationships. She was destined to live alone with her adopted children. Mary's

lifestyle consisted of a mud hut (infested with roaches, rats, and ants), irregular daily schedule

(normal in African culture), and simple cotton clothing (instead of the thick petticoats and

dresses worn by most European women at the time). Other missionaries were unable to relate

to her life. Although she suffered from malaria occasionally, she outlived most of her missionary

co-workers.

Mary Slessor was 55 when she moved on from Okoyong with her seven children to do pioneer

work in Itu and other remote areas. She had much fruit with the Ibo people. Janie, her oldest

adopted daughter, was a valuable asset in the work. For the last ten years of her life, Mary

continued doing pioneer work while others came in behind her. Their ministry was made much

easier because of her efforts. In 1915, nearly 40 years after coming to Africa, she died of fever

at the age of 66 in her mud hut. Mary Slessor has become an inspiration to all who hear her

story. She was not only a pioneer missionary, but also a pioneer for women in missions.

CT Studd (1860-1931)

"Some wish to live within the sound of Church or Chapel bell; I want to run a Rescue Shop within

a yard of hell."—CT Studd

Charles Thomas Studd was born in England in 1860, one of three sons of a wealthy retired

planter, Edward Studd, who had made a fortune in India and had come back to England to spend

it. After being converted to Christ during a Moody-Sankey campaign in England in 1877, Edward

Studd became deeply concerned about the spiritual welfare of his three sons and influenced

them for the cause of Christ before his death two years later.

By the time Studd was sixteen he had become an expert cricket player and at nineteen was

captain of his team at Eton College. He was further educated at Trinity College, Cambridge

where he was also recognized as an outstanding cricketer. He played for England in the 1882

match won by Australia which was the origins of the Ashes.

Studd was saved in 1878 at the age of 18. After six years in a backslidden state, but was

restored to faith when he went to hear the American evangelist DL Moody.

Studd decided to go to China as a missionary (1885). Once there, he followed the early practice

of the Mission by living and dressing in Chinese fashion. At 25 he gave away an inheritance he

had received from his father's estate. He and his wife served in China until 1894.

In 1900 the Studd family went to South India where he served as a pastor of a church in

Ootacamund for six years. From the time of his conversion, Studd had felt the responsibility

upon their family to take the Gospel to India. After their return home to England in 1906, he

was stirred by the need for missionary pioneer work in Central Africa. Penniless, turned down

by the doctor, dropped by a Committee of businessmen who had agreed to support him, yet told

by God to go, once more he staked all on obedience to God. Leaving his wife and four daughters

in England, he sailed to Africa in 1910. He endured weakness and sickness; loosing most of his

teeth and suffering several heart attacks. He died in July 1931

- "Only one life, 'twill soon be past, only what's done for Christ will last."

One of Studd's enduring legacies is WEC, which he founded in 1913. The organization began as

the Heart of Africa mission, changing its name to Worldwide Evangelization Crusade. Later,

recognizing some misunderstandings with using the word "crusade", the mission was renamed as

Worldwide Evangelisation for Christ (WEC International.)

Jim Elliot (1927-1956)

Jim Elliot always wanted to be a missionary. He grew up in a family that read the Bible each

day and lived a Christian lifestyle. He went to college with his focus on those activities which

would help him to be a missionary. After he graduated, he had an opportunity to go to Ecuador

to work amongst the Quechua Indians and did so in 1952 with a friend named Peter Fleming. For

more than three years they worked amongst the people establishing a missionary post and an

airstrip. He married Elisabeth Howard in 1953.

In 1955 Elliot and four friends (Ed McCully, Nate Saint, Roger Youderin and Peter Fleming) began

attempts to get to know the mysterious Auca tribe, living in the Ecuadorian jungle. They

decided to start gaining their confidence by dropping gifts from Nate Saint's aeroplane.

Eventually they agreed that the time was right for them to go into Auca territory. They flew in

and established a base, after which they made initial contact with members of the tribe. That

was the last time their families heard from them. All five were killed near their aeroplane.

To many people it seemed that Jim Elliot's dream and the aspirations of the other men had

ended in failure. Amongst personal possessions recovered was a camera, and amongst the

pictures taken were some of the Auca Indians who had initially made contact with the

missionaries. The people in the photographs were recognized by an Auca woman who had

helped the missionaries learn the language. They were relatives that she thought were dead.

Before long Elisabeth Elliot and Rachel Saint (Nate's sister) were living amongst the tribe. They

established a church and many of the Aucas became Christians. Elisabeth Elliot returned home

to America after several years; she subsequently produced a number of best-selling books.

Rachel Saint stayed with the Aucas for many years. Marilou McCully set up a school for

missionary children in Quito. Barbara Youderin went to work with another tribe.

The story of Jim Elliot, Ed McCully, Nate Saint, Roger Youderin and Peter Fleming has become

one of the great missionary accounts of the 20th century.

- "He is no fool who gives what he cannot keep to gain that which he cannot lose."

- "I seek not a long life, but a full one, like you Lord Jesus."

- "God always gives his best to those who leave the choice with him."

Christianity in Australia

English and European settlers and convicts brought their Christian traditions with them to

Australia. The first Anglican clergy arrived in 1788; Methodist in 1815; Catholic in 1820;

Presbyterian in 1822; Congregational in 1830 and Baptist 1834. Other early groups included

German Lutherans.

In 1901, 74% of population of Australia identified as Protestant and 23% as Roman Catholic. By

the end of the Century, there were significant changes in Christian affiliation reflecting changing

immigration patterns and Charismatic movements (with their own missions emphasis). After

WWII, there was a rapid growth in Eastern Orthodox churches and Catholicism. More recently,

many more migrants have often come from non-Christian backgrounds. By 2000, 43% of

Australians identified as Protestant, 27% as Roman Catholic, and 3% as Eastern Orthodox.

Recent Developments

In 1800, perhaps 1 per cent of Protestant Christians lived in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. By

1900, this number had grown to 10 per cent. Today, at least 67 per cent of all active Protestant

Christians live in countries once considered foreign mission fields. The church in Europe has

diminished in importance and influence, but it is still growing rapidly, even explosively, in many

areas normally identified as "the developing world", in particular sub-Saharan Africa and China.

Only 200 years ago, Protestant Christianity was almost exclusively Western. Now Protestants are

strongest in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. From a Christian standpoint, the modern missionary

movement has turned the world upside down and has impacted the church growth movement.

In the 1800s, with rare exceptions, cross-cultural missionaries came from the West. Even until

forty years ago being a missionary generally meant a Westerner going to Asia, Africa, and Latin

America. Today, the number of cross-cultural missionaries is growing most rapidly among

believers in these regions. This is a new phenomenon in history.

NO MESSAGE HAS BEEN COMMUNICATED SO WIDELY BY SO MANY PEOPLE OF SO MANY RACES,

LANGUAGES, AND CULTURES AS THE CHRISTIAN MESSAGE TODAY. SOME COUNTRIES/CULTURES

OFFICIALLY REMAIN "CLOSED", BUT ARE BEING REACHED THROUGH BRAVE BELIEVERS AND

GLOBALLY REACHING TECHNOLOGIES.

Lausanne Movement

In 1966 the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, together with Christianity Today, sponsored

the World Congress on Evangelism in Berlin. This gathering drew 1,200 delegates from over 100

countries, and inspired conferences in Singapore (1968), Minneapolis and Bogotá (1969), and

Australia (1971). Shortly afterwards, Billy Graham identified the need for a larger, diverse

congress to re-frame mission in a world of social, political, economic, and religious upheaval.

The Church had to apply the gospel to the contemporary world, and to understand the values

behind changes in society. In July 1974 2,700 participants from over 150 nations gathered in

Lausanne, Switzerland, for ten days of discussion, fellowship, worship and prayer. Given the

range of nationalities, ethnicities, ages, occupations and church affiliations, TIME described it as

'a formidable forum, possibly the widest ranging meeting of Christians ever held'.

Speakers included some of the world's most respected Christian thinkers of the time. The

introduction of the term 'unreached people groups' was hailed as a missions milestone. Some

Christian organizations were calling for a moratorium on missions, but it was recognised that

thousands of people groups remained without a single Christian, and with no access to the Bible

in their own language; cross-cultural evangelization needed to be the primary task of the

Church. A major achievement of the congress was to develop The Lausanne Covenant. Since the

first congress there have been many large conferences under the Lausanne umbrella.

Other developments:

- 10/40 Movement - In 1990 Christian strategist Luis Bush coined the term "10/40 Window,

a rectangular area of North Africa, the Middle East and Asia between 10 degrees north

and 40 degrees north latitude. Often called "The Resistant Belt", it includes the majority

of the world's Muslims, Hindus, and Buddhists. An estimated 4.7 billion individuals reside

in approximately 8,749 distinct people groups in the 10/40 Window. The 10/40 Window is

home to some of the largest unreached people groups in the world.

- Increase in Bible societies and translations

- Youth with a Mission (founded by Lauren Cunningham)

- Reaching the world using enhanced technology: http://www.relevant-christianity.com/pdf/ministry/Sustained_World_Mission_in_a_Networked_Age_-_Trends_.16961124.pdf

- Emphasis on indigenous leadership

- Growing cross-cultural mission, especially in migrant intake countries.

- Tent-making and "short term missions"

Issues Facing Christians During this period

- Getting Christians out of comfort zones (some of which were theologically based). Many

Western Christians saw Christianity as "their" religion.

- Grasping the gap between God's purpose of world evangelization & the fulfillment of it.

- "Some are trapped in boxes of pea-sized Christianity, full of myths about missions

that rob them of incentive to care about the unreached." (David Bryant,

Perspectives, D305)

Taking people the Gospel in words they could understand (the vernacular).

The focus of the Christian missions community 200 years ago was for the coastlands of

the world. A century later, the success of this effort motivated a new generation to

reach the interior regions of the continents. Within the past several decades, the success

of the inland thrust has led to a major focus on "people groups".

Dealing with lengthy timeframes before mass conversions (Livingstone, Judson;

challenges of outreach in Muslim societies).

Adoniram Judson (1788-1850) waited six years before the first Burmese came to know

Christ. By the time of his death, there were 63 churches and 7,000 converts. Of the

Karen peoples, there were 800 churches and 150,000 believers.

3 Cs -Confusing Christianity with Civilization and Commerce ("The suasion of the sign").

Dealing with opposition and hindrance by colonists who feared upsetting Hindus, Muslims

and other colonial populations and damaging colonial administration and trade.

Syncretism.

Overcoming stereotypes about Western imperialism and dominance.

Dangers of missionaries being targeted by revolutionary or independence movements.

Acknowledging the validity of raising up indigenous leadership.

Cultural paradigm shifts.

- Hudson Taylor was disillusioned with Protestant missionaries in China who lived in

compounds and employed indigenous people as servants. He learned local

dialects, adopted local dress, and went up China preaching. He sought to

distance himself from paternal organizations and denominations in favor of "faith

missions" that relied on local support. He sought to train indigenous leaders to

lead churches and missions in China, rather than have them run by foreigners.

"All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore go and make disciples of

all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and

teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to

the very end of the age." (Matthew 28:18-20)

Additional Reading

Anderson, C, To The Golden Shore: The Life of Adoniram Judson, Zondervan Publishing House, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 1972

Blainey, G, A Short History of Christianity, Viking, Melbourne, 2011

Dowdy, HE, Out of the Jaws of the Lion: Christian Martyrdom in the Congo, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1965

Elliot, E, Through Gates of Splendour, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1957

Elllis, JJ, Hudson Taylor of China: A Little Man Who Did Great Things for God, Pickering and Inglis, London

Hesselgrave, DJ, Communicating Christ Cross-Culturally: An Introduction to Missionary Communication (2nd Edition), Zondervan Publishing Ghouse, Michigan, 1991

Lion, A Lion Handbook, 1990, The History of Christianity

Renwick, AM, The Story of the Church, Intervarsity Press, Edinburgh, 1973

Winter, RD, Perspectives on the World Christian Movement (Revised Edition), The Paternoster Press, Carlisle, United Kingdom, 1992